Monopoly, Mississippi, Metropole: The Case for American Autocolonialism

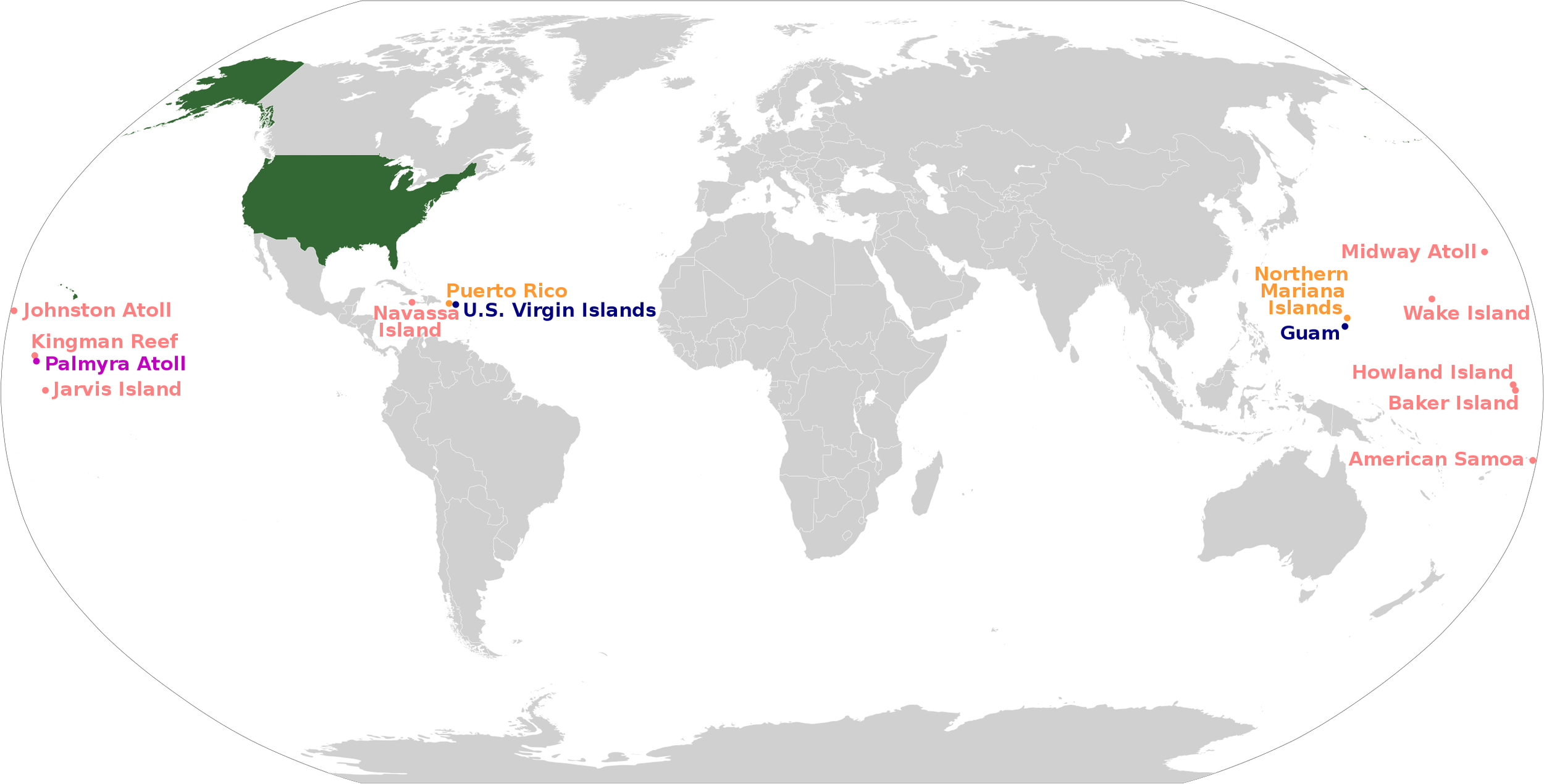

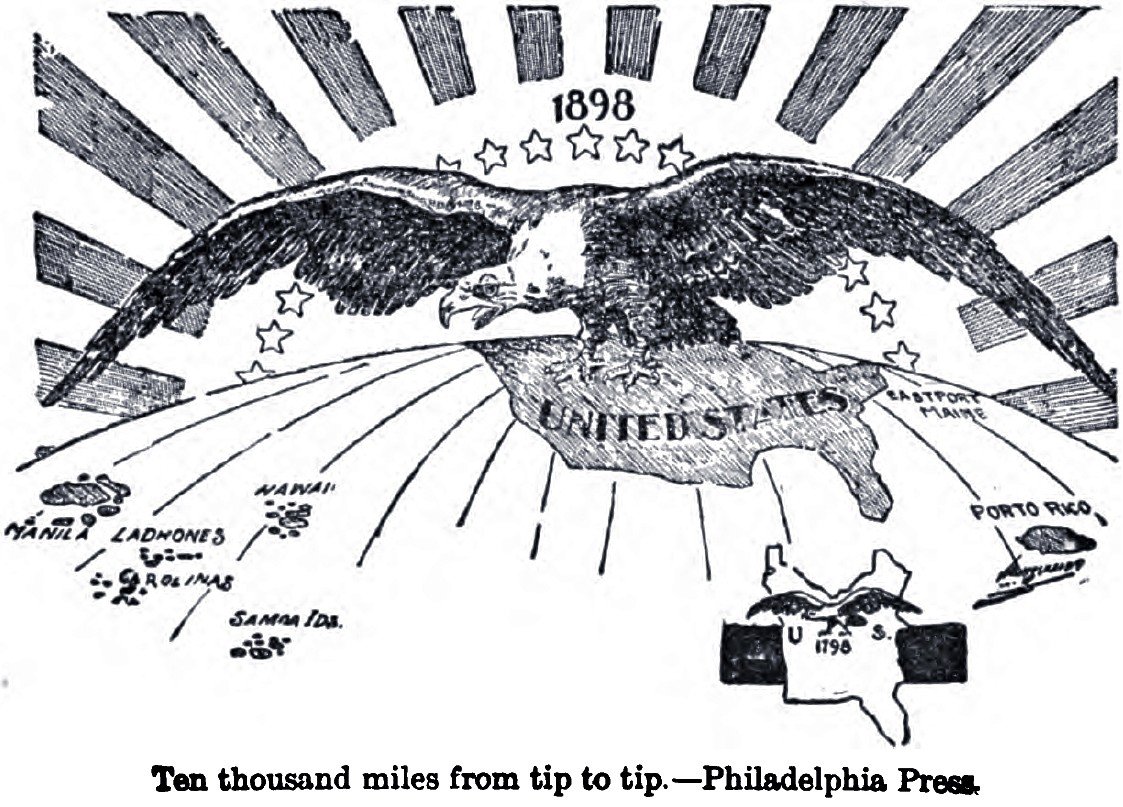

Controlling Puerto Rico, Guam, Hawaii, the Mariana Islands, and even parts of Samoa, the United States has often been described as a colonial power. But America’s real colonial holdings extend beyond its handful of island territories—indeed, they include cities inside its own borders. Just look at Jackson, Mississippi.

Jackson is a city overcome by rampant inequality and seemingly forgotten by the rest of the United States. Surrounded by majority-white, upper-middle-class suburbs, downtown Jackson has fallen into disrepair. Poorly paved and severely lacking capital investment, Jackson is economically hopeless, with its sidewalks speckled with potholes and its industry dominated by low-paying service jobs. Indeed, Mississippi scored lowest of all 50 U.S. states on the Social Progress Index, a survey of socioeconomic development measuring education quality, crime rates, the robustness of infrastructure, and other indices of a state’s wellbeing. Economically, Jackson is an example of what will hereafter be referred to as “autocolonialism,” a city or region of a country that is economically colonized by its parent state.

Critically deprived of the robust education system central to fostering a competitive economy, Jackson’s human and monetary capital is funneled into cities in its parent nation such as New York City, Los Angeles, or Chicago, who work for the same colonial power that has suppressed and profited off of the city for so long. To that end, the U.S. feeds on Jackson much like how any colonial power profits off of its colonies: not unlike how an infection feeds on an otherwise healthy body, sucking, in this case, the economic lifeblood out of the city without giving it the economic infrastructure it needs to become economically self-sufficient and healthy once again. Jackson thus resembles a colonial holding of the rest of the United States, pillaged by the metropole for its resources, reliant on its parent nation for survival, and critically lacking the investment in education it needs to foster the competition conducive to economic rebirth.

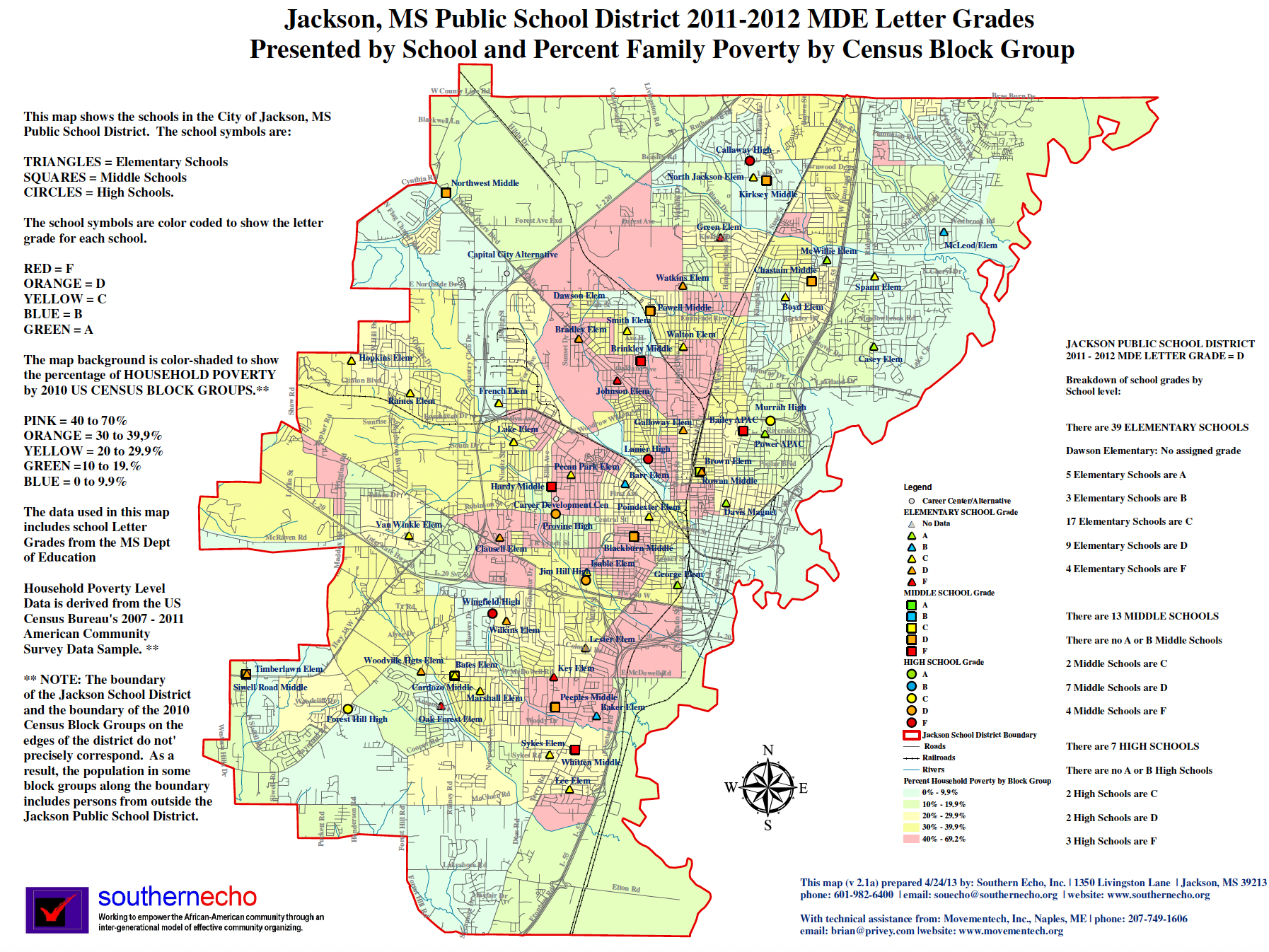

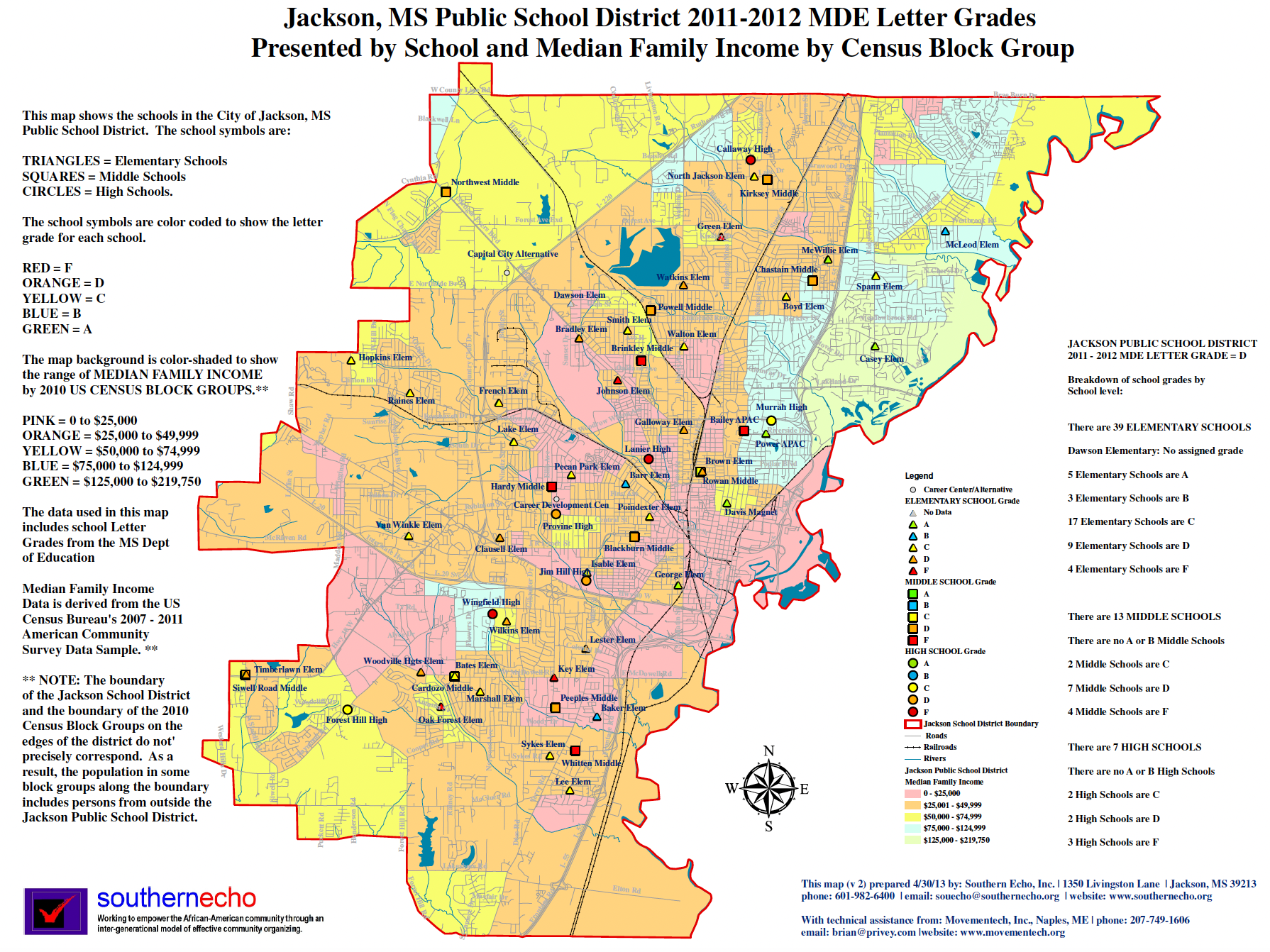

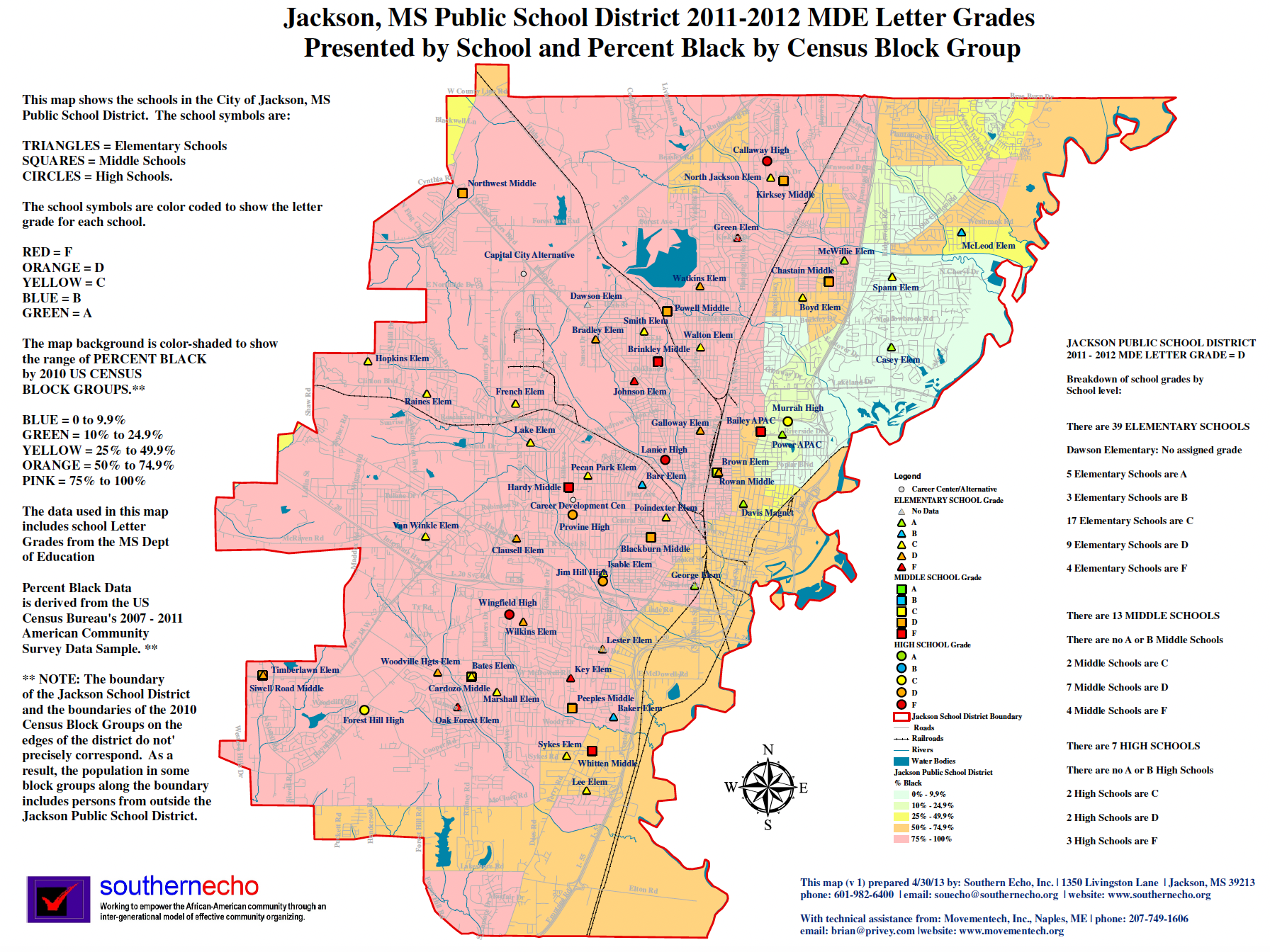

As an autocolonial holding of the United States, Jackson’s economic problems are many, but they all stem from one single starting point: access to a high-quality education, which is, in this case, the duty of the metropole to provide. The chief goal of any government—including the United States when it comes to Jackson—should be to provide its citizens with the means through which they can economically sustain themselves. This includes education and the presence of vital economic infrastructure. Investment in education and infrastructure fosters a healthy, diversified, and thriving economy by creating competition—if everyone has equal resources for betterment, everyone can become wealthy. The United States, though, is far from providing Jackson’s schools the proper funding and materials they deserve: classrooms lack basic supplies, the hallways are dark and dingy, the cafeterias serve food past its due date, and school administrators severely limit and even restrict access to computers.

All of these problems may not seem directly related to the quality of instruction, but they undeniably affect student performance: according to the Social Progress Index, which measure metrics of societal wellbeing, the United States ranks only 44th in the world in terms of school-level education, with Mississippi scoring the lowest of all 50 states. As a result, Jackson’s economic output is severely affected, as students are poorly prepared for college and thus unequipped to contribute to Jackson’s economy and foster competition. Furthermore, as is consistent with colonies, those graduates that do succeed, given the lack of high-paying jobs in Jackson, will simply move to the metropole, creating a massive brain drain. Since the duty of the U.S. government is to provide Jackson with the economic frameworks it needs for its citizens to thrive, it has utterly failed, since a well-educated populace is the lifeblood of any healthy economy. Thus, Jackson resembles a colony: seemingly trapped in a form of educational and intellectual mercantilism, Jackson’s school system receives little to no support from its parent country, all while losing its greatest asset—its citizens—to the metropole.

Financially, Jackson resembles a colony since it is dominated by large, multinational corporations whose profits benefit those who live in the metropole, not in Jackson. As was true with the British Empire in America and the West Indies, colonies subject to monopolies do not benefit the colonists, they instead only make profit for a small number of elites in the metropole. As was also the case in the Americas in the 18th century, monopolies hinder the key element of competition which is not only integral to the free market but also a state’s duty to foster. Just like Belgium extracting rubber from the Congo, the American colonial system rapidly takes capital out of Jackson with little to no reinvestment—America’s multinational corporations, whose dominance has in part created the inequality that plagues Jackson, profit off of the city’s poor. Deprived of economic competition and therefore devoid of small businesses, Jackson is a food desert, where a lack of grocery stores mean that massive companies utterly dominate the city’s food market. As people buy more food from these companies, they only send more money back to the wealthy cities of the metropole, instead of keeping the money invested in the community and centralized in Jackson.

Indeed, the Jackson water crisis of 2022 underlined the hegemony of big business over Jackson. As taps ran with brown water and Jacksonians struggled to drink, cook, and bathe, water companies raked in the profits. To deal with the crisis, the city purchased water en masse from brands like Niagara, Kroger, and Great Value. Not only are all these companies based in places outside of Mississippi, but they are also owned in part and in full by supermassive entities, such as Walmart (Great Value), BlackRock (Niagara), and Vanguard (Kroger). As awful as the Jackson water crisis was, it was lucrative for big water—all at the expense of the city.

Like a rapacious colonial superpower, the United States is simultaneously at fault for Jackson’s problems yet profiting off of Jackson’s helplessness. The divestment that creates a food desert is the precise reason that large grocery stores have monopolies in Jackson or why the massive companies sell their water to the city; since people must eat and drink, it is a monopoly fueled by desperation and one that only benefits the metropolitan elite. Historical examples of this include French colonies in the 19th and early 20th centuries, where the economy was dominated by a white French and mixed Franco-Senegalese merchant class who profited off of the poverty and desperation of many, all while furthering French interests in West Africa.

Jackson is thus situated firmly in the economic periphery of the American system. Experiencing a brain drain because of divestment and poverty, the city loses the human and financial capital it needs to thrive in exchange for the consumer goods it needs to survive. The U.S.-Jackson relationship is like a form of the colonial mercantilism of centuries past, where African nations on the periphery would export raw materials to Europe only to be sold the cheap goods whose materials their labor extracted.

The dependency theory of imperialism, whereby a colony, situated on the periphery, feeds its parent nation at the core.

On a local level, the colonial analogy remains true: racism and white flight to the suburbs have created a ring of wealth around Jackson, further depleting it of resources, drawing funding away from its schools, and hindering the city’s ability to nourish an educated populace and a thriving economy. Since the 1930s, redlining has plagued Jackson, where traditionally black regions in the city were redistricted, or “redlined” so that they would receive less investment than their white counterparts. This racially motivated practice was disastrous for Jackson’s economy, as the same regions that are poorest in Jackson today were districts that were redlined. Equal application of justice and law should govern economics; it is, therefore, important that laws do not constrict economic trade or reserve it for a certain race, but simply guide it in a safe, equitable, and reasonable direction. To that end, the U.S. government has failed the city of Jackson and served its majority-white suburbs by enacting racist policies which stifle the competition crucial to a free market economy. The divestment of human capital Jackson experiences on a national level extends to a regional sphere, as well: white families have left Jackson seemingly en masse, enrolling their students in nearby private schools equipped with better amenities. Indeed, Jackson’s school district has lost 8,000 students in the last decade, and their families—and the revenue for local business that they bring—have left with them. Just as Jackson suffers from a brain drain on a national level, since a colony will always export the commodity it can best provide, Jackson also experiences a severe loss in human capital on a local scale. Therefore, the colonial model applies locally to Jackson as well, since it loses its resources—human capital and the business it brings—to its surrounding area, and those emigrants do not reinvest in the city. Despite being surrounded by wealthy suburbs, Jackson is, in an autocolonial sense, firmly in the periphery of its own economic system.

In matters relating to education, finances, and suburban relations, Jackson is an autocolonial possession of the United States—the U.S. has seemingly established a colonial relationship with one of its own cities. Since the U.S. fails in its duty to provide access to a quality education, it deprives Jackson of the fundamental element of economic competition that the city needs to thrive, all while extracting Jackson’s brightest minds in a form of modern-day intellectual mercantilism. Indeed, much like a colonial power, the United States—and its massive corporations—profit off of a grocery store monopoly over Jackson, and let the poor, hungry desperation of Jacksonians fill the coffers of the wealthy metropolitan few. Locally, the suburbs of Jackson serve as a microcosm of American autocolonialism, leveraging existing racist policies like redlining to deplete Jackson’s school system and impede Jackson’s chances at spurring economic competition. For Jackson’s wealth to increase, the government must endow the city with an adequate education system, which will foster the competitive atmosphere conducive to economic growth. This can be achieved through renovating school buildings, working to attract more talented teachers, and establishing a different style of teacher pay, which would be measured by student improvement on metrics such as standardized test scores and improvement in grades from semester to semester. Jackson’s growth can come from within the periphery, but it must be catalyzed monetarily by the “core” through investment in tangible, fixable sectors. The British colonial system, admittedly, was free from many of the downsides of colonialism, but no colonial power can hope to establish a system of mercantilism or extractive trade without expecting to benefit the metropole and impoverish the colony. To that end, any historically poor city in the U.S. can serve as a stand-in for Jackson, since inequality and autocolonialism in America, after all, is not just present in Mississippi alone.